Meiji Shippo - The Golden Age of Cloisonné

We are pleased to share an introduction co-written with our dear friend and esteemed colleague, the late Gregory Irvine, for the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum's publication, ‘Meiji Shippo – The Golden Age of Cloisonné’ published alongside their exhibition last year. The Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum houses one of the world's finest collections of cloisonné enamelwork, featuring exceptional examples of this intricate art form. The remarkable craftsmanship and historical significance of these pieces deserved to be celebrated and we are pleased to share our introduction alongside images from this extraordinary collection

Meiji Shippo – The Golden Age of Cloisonne

Published in conjunction with a Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Art Museum Project, Kyoto, 2025

“The development of Japanese enamels in the later Meiji period and their reception in the West”

Malcolm Fairley - Japanese Works of Art, Bury Street, St James's, London

Gregory Irvine - Honorary Senior Research Fellow, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

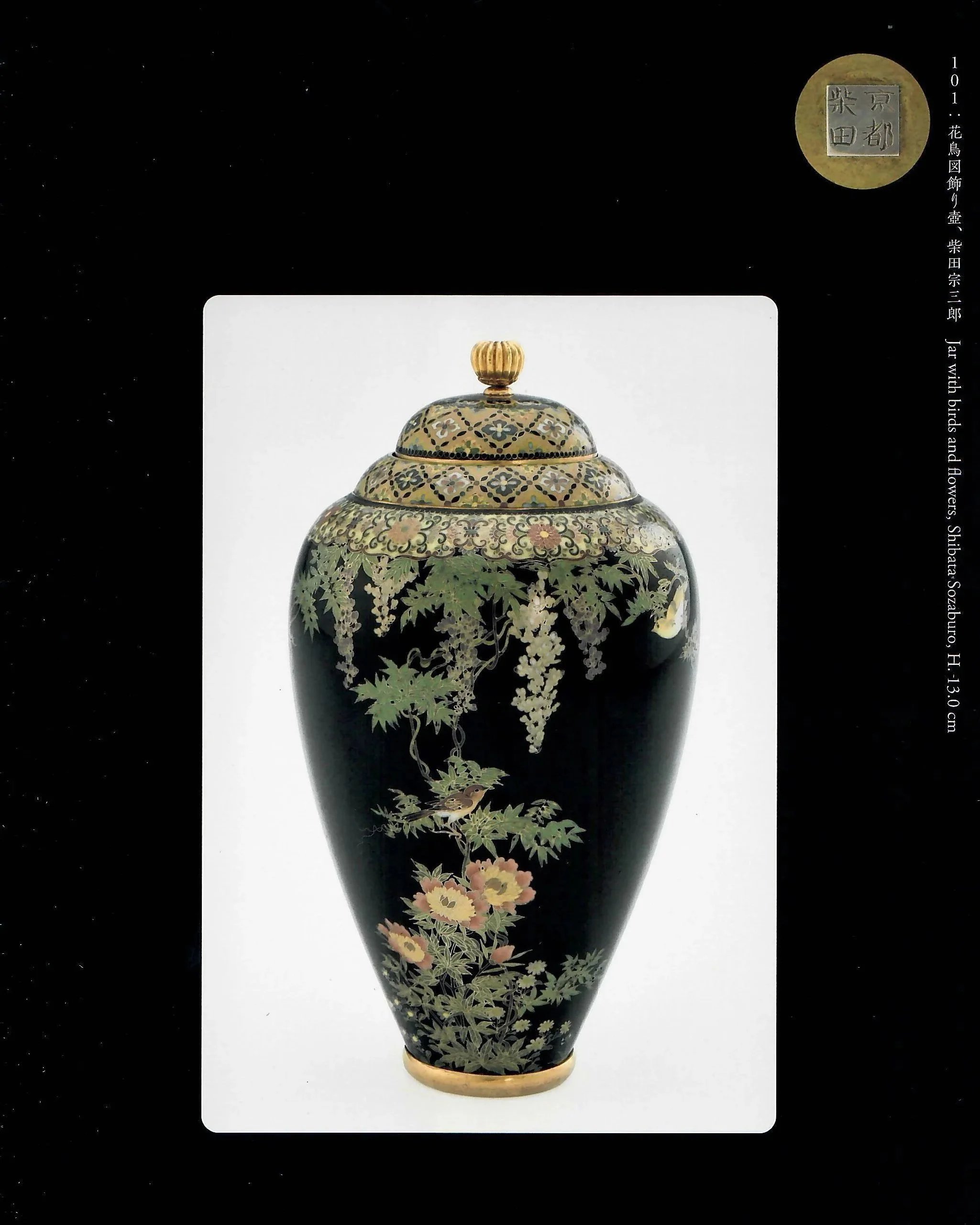

This book does not attempt to show a representation of the history and development of Japanese cloisonné enamels, rather it shows a connoisseur's choice and curation of the finest enamels produced from the period approximately 1885-1912. Mr Murata has only ever chosen the highest quality works by the most skilled and talented makers to become part of his collection. The highlights to be found in this book are the works by the two Namikawas - Yasuyuki and Sōsuke - both of whom were given the title of Teishitsu Gigei’in by the Emperor Meiji. Other examples of this superb craft in the collection include cloisonné objects produced by the many makers to be found in and around Nagoya where enamelling had its revival around 1840. The collection also includes smaller examples of cloisonné enamels made in the later Edo period as decoration on sword fittings, notably those of the Hirata School.

The renaissance of Japanese cloisonné manufacture is credited to Kaji Tsunekichi (1803-83) of Nagoya in Owari province, a former samurai turned metal-gilder. Like many increasingly disenfranchised samurai of the early nineteenth century, he was required to find ways to supplement his meagre official stipend. It is believed that around 1838 Kaji acquired a piece of Chinese cloisonné enamel and, by deconstructing it eventually produced a small cloisonné-enamel dish. Then, according to a summary of Kaji’s own account of his career, 'He now applied himself with patient assiduity to work of this kind, and succeeded, in 1839, in making a plate six inches in diameter'.[1] Kaji produced other small items, such as brush-rests and cups, and soon 'had the honour of seeing his productions presented to the Tokugawa Court in Yedo by the feudal chief (daimyō) of Owari'.[2] By the late 1850s, he had been appointed official cloisonné maker to the daimyo of Owari.

His designs mostly used the motifs and colour schemes of Chinese cloisonné enamels. Early works are characterised by the use of many background wires that were both decorative, in that they formed an integral part of the design, and practical in that they prevented the enamels from running during the firing process.

Following the London International Exhibition of 1851, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) was established with the purpose of forming collections that would 'exhibit... the practical application of the principles of design in the graceful arrangement of forms, and the harmonious combination of colours for the benefit of manufacturers, artisans and the general public’.[3] The Museum's first acquisition of cloisonné enamels came from the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867: these are the earliest documented examples of Japanese cloisonné enamels in the West, and indeed in any world museum. They were a ‘kettle’ (chōshi) bought for £24, and a ‘sweetmeat case' (jūbako), for which the extraordinary sum of £60 was paid described as 'antique Japanese'. The high prices paid are indicative of the appreciation of this new form of Japanese art, never before seen in the West and which provided a wonderful resource for the study of this hitherto unknown form of Japanese craftsmanship.

International exhibitions were occasions whereby Japan could show the world its skills in the arts, crafts and other manufacturing industries, and Japan sent both official and unofficial delegates to the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867. The displays were a phenomenal success and over nine million people attended the exhibition: the craze in Europe for things Japanese had begun. Japan's next major contribution to international exhibitions was at the Vienna International Exposition of 1873. This was the first official participation in a world exhibition by the new Meiji government and the Japanese displays were diverse although they were presented in a way designed to appeal to western taste.[4]

Following the 1873 Vienna International Exhibition, which was visited by over seven million visitors, Japanese art objects had made a deep impression on the European art scene with collectors and manufacturers being inspired by the forms and designs they were now encountering. It was not only in Europe that enamels were being exhibited. Namikawa Yasuyuki exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 where he was awarded a medal for his work. The Paris International Exposition of 1878 built upon earlier successes and attracted an astounding sixteen million people. The craze for Japan and the fashion for Japonisme in Europe were now at their peak.

Japanese at was now being imported in enormous quantities and sold through specialist dealers and shops in London such as Liberty's, Yamanaka (who had shops in several countries) and in Paris through shops such as La Porte chinoise and Bon Marché. In Paris, the German-born dealer Siegfried Bing was one of the foremost promoters of the arts of Japan and it was from his shops that many collectors, museums and artists acquired Japanese works of art. Across the world, as far apart as the USA and India too, dealers sprung up to cater for the demand from discerning collectors for fashionable Japanese art works, especially enamels.

In 1878, Sir Rutherford Alcock, one of Britain's first diplomats in Japan (and organizer of the Japanese display at the1862 London International Exhibition commented admiringly on cloisonné enamels:

Their patterns are generally intricate and minute, small sprays, flowers, diapers, and geometrical figures all being laid under contribution, while leaves of various colours - drab, white, light green - are interspersed. These being minutely subdivided, it is impossible not to be struck with admiration at the marvellous delicacy of execution and fertility of invention, if not of imagination, displayed. Such works would simply be unproducible in any country where skilled workmanship of a high order, and artistic in kind, was not abundant and obtainable at exceedingly low rates of remuneration. Many of the enamel works must represent the labour of years, even for two or three hands'.[5]

The Scottish designer Christopher Dresser (1834-1904) had played a significant role in disseminating the understanding of Japanese art in Britain. He wrote and lectured on Japanese art, imported it as a dealer, and in 1876 was the first European designer to visit Japan (on behalf of the V&A and the British government) where he made a thorough study of the crafts and manufactures of Japan and subsequently wrote about his experiences.

He designed and produced objects that were influenced by what he saw as the simplicity and boldness of form to be found in Japanese art. He advised Londos & Co. who provided many Japanese art works for western museums as well as for companies such as Tiffany's of New York.

In 1880, the V&A acquired several items from Londos and Company, most likely pieces acquired by Dresser on his visit to Japan. Two pairs of small, unsigned vases look to be, on stylistic grounds, early examples of the work of Namikawa Yasuyuki. That they might be of Kyoto origin was suggested by Hayashi Tadamasa (1853-1906) when he visited the V&A in 1886 to assess the Japanese collections. Hayashi had served as an interpreter at the 1878 Paris Exposition but stayed on in to become an important dealer and adviser on Japanese art.

With the introduction of advanced enamelling techniques from Europe the previous reliance on background wires to retain the enamels was removed and the way was open for the possibility of using larger areas of clear bright enamels. The Ahrens Company in Tokyo was one of many companies set up under the new Meiji government's programme whereby western specialists were invited to Japan to help modernise the country's existing industries. The chief technologist of the

Ahrens Company was the German chemist Gottfried Wagener (1831-92). Wagener, an expert on glazes and firing techniques, was responsible for many of the key innovations on which the subsequent success of the Japanese cloisonné enamel industry was to depend.

The Japanese-German collaboration gave rise to new enamels with a wider range, depth and intensity of colours. Finishes were improved and far higher levels of gloss were achieved than had been previously possible. Innovations introduced by Wagener obviated the need for background wires to retain the enamels, the way thus being opened for the application of clear bright enamels over large unbroken areas of the vessel surface. No longer were potentially distracting patterns of circles, abstract patterns and karakusa scrolls required for technical reasons: the creation of more realistic and painterly designs in enamels was now possible.

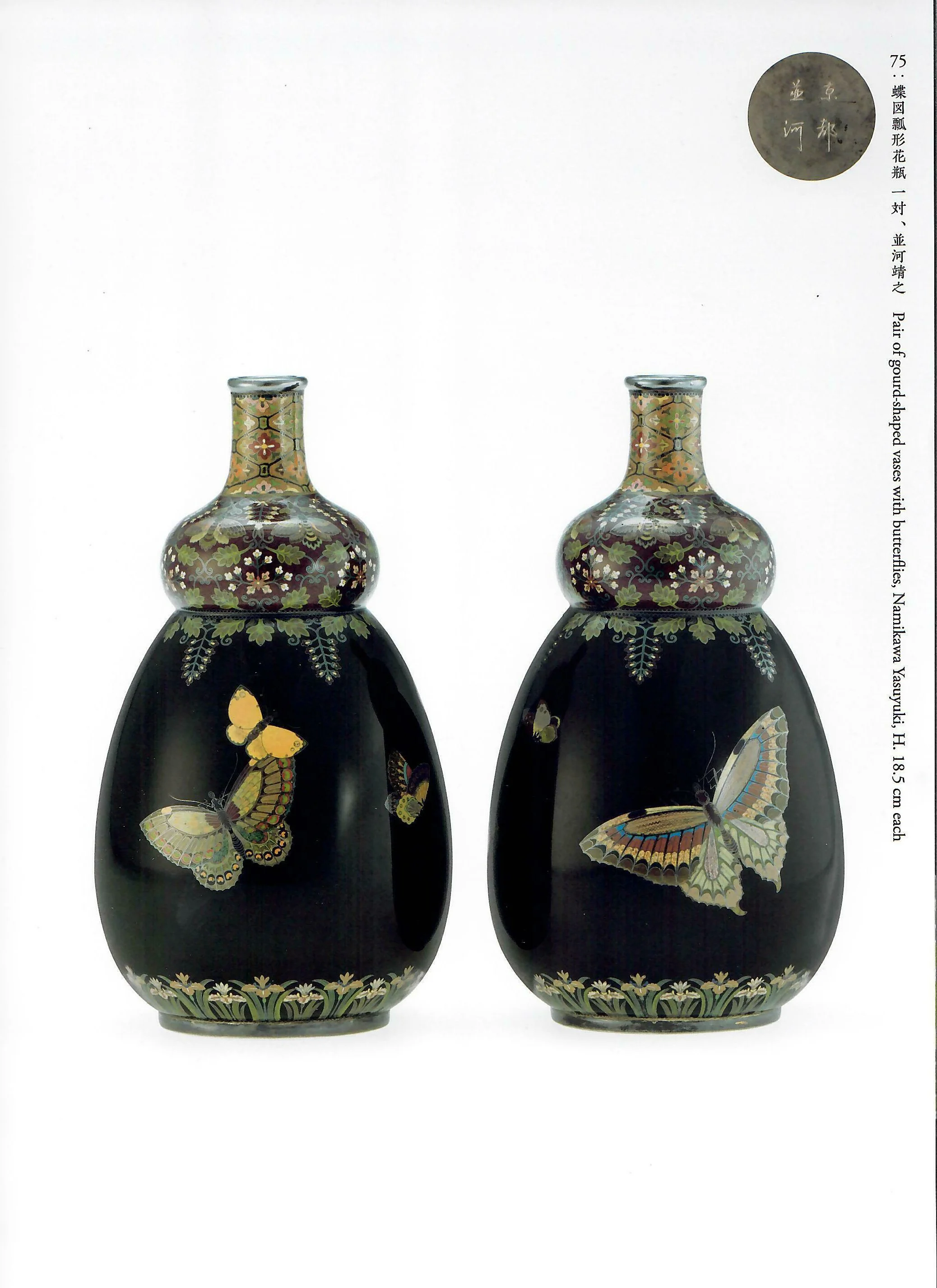

In 1878 Wagener moved to Kyoto where he met the former samurai and cloisonné artist Namikawa Yasuyuki (1845-1927). Although it is not clear exactly how Wagener and Yasuyuki met, there is no doubt that they collaborated and that one of the most significant results of their collaboration was the creation of the superb semi-transparent mirror black enamel that was to become the hallmark of much of Yasuyuki's subsequent work. However, these innovations took time to perfect and the use of fine decorative wires also remained integral to the cloisonné enamels of Yasuyuki.

Yasuyuki is believed to have started his career around 1868 and worked with the Kinunken group of the Kyoto Shippo Kaisha from 1871: he left them in 1874 and set up own his studio. By 1875, he was exhibiting his work at national and international expositions including the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia 1876, the First National Industrial Exposition Tokyo 1877, Exposition Universelle de 1878, Paris and the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago in 1893.

Yasuyuki's enamels are characterised by the skilful use of fine and incredibly detailed wirework and superb attention to detail, both being greatly admired by the many western travellers and collectors of the late nineteenth century who visited his studio and workshop in Kyoto. These travellers included the writer Rudyard Kipling and although Kipling does not mention Yasuyuki by name it is obvious that it is his workshop he is visiting

‘It is one thing to read of cloisonné making, but quite another to watch it being made... With the finest silver ribbon wire, set on edge, less than a sixteenth of an inch high, he followed the lines of the drawing at his side, pinching the wires into tendrils and the serrated outlines of leaves with infinite patience... With a tiny pair of chopsticks, they filled from bowls at their sides each compartment of the pattern with its proper hue of paste... I saw a man who had only been a

month over the polishing of one little vase five inches high. There is also cheap cloisonné to be bought," said the manager with a smile. "We cannot make that. The vase will be seventy dollars. I respected him for saying ‘cannot’ instead of 'do not’. There spoke the artist.’ [7]

Perhaps the most extensive descriptions of Yasuyuki and his workshop are to be found in `In Lotus Land Japan’, written by Herbert Ponting. He devotes an entire chapter to Yasuyuki and creates a somewhat romantic view of the conditions of cloisonné production. He begins ‘Here I met Mr Namikawa. A man of quiet speech and courteous manner, whose refined classical features betrayed the artist. [8]

Ponting gives his impression of how Yasuyuki's workshop operated: ‘Namikawa himself attends to the firing – perhaps the most important part of the whole process, for on it depends the success or failure of all the work preceding it…Namikawa's artists do not work by set hours, but only when the mental inspiration is upon them...’ [9]

Confident of his skills and assured of a market for whatever he could produce, Yasuyuki continued to make cloisonné enamels with designs predominantly defined by wires but also pieces where the pictorial composition was balanced by large areas of pure coloured enamel. In 1896, he, along with Namikawa Sōsuke (1847-1910), was appointed Teishitsu Gigei’ in (Imperial Court Artist).

Namikawa Sōsuke (the name Namikawa here being written with different characters from those used by Yasuyuki) originally worked for the Nagoya Cloisonné Company but moved to run their branch of the company in Tokyo. By the early 1880s Sōsuke was exhibiting at national and world expositions, including the Universal Exposition, Amsterdam, in 1883 and the Nuremberg International Metalwork Exhibition of 1885 where he was awarded prizes for his work, He was awarded the Grand Prix' at the Exposition Universelle, Paris 1889.

Sōsuke's style involved enamelling using fewer or partial wires (shōsen) and eventually there was no apparent use of wires at all (musen). This enabled him to produce enamelled objects giving the impression of reproductions of paintings in ink. These techniques were difficult and demanded great skill on the part of the enameller but were greatly admired by both western and Japanese collectors. Sōsuke reproduced woodblock prints and paintings in enamels, working closely with contemporary artists, notably Watanabe Seitei (1851-1918). At the World's Columbian Exhibition of 1893, Sōsuke exhibited his famous Mount Fuji among the clouds', a large plaque in wireless shaded enamels, now in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum. This popular motif was repeated by Sōsuke in other versions of the plaque as well as being copied by other enamel manufacturers.

The period from around 1880 to about 1910 has been referred to as the ‘Golden Age' of Japanese enamels when production and technical innovation were at their peak. There were hundreds of makers and companies working to satisfy the demand for enamels, mostly produced for the western market. In 1911 Professor Harada Jirō wrote as follows:

There are two distinct qualities or types expressed in Japanese art: one suggesting endless patience in the execution of minute detail, the other denoting a momentary conception of some fleeting idea carried out with boldness and freedom of expression in form and line - profuse complexity and extreme simplicity... the work on Japanese cloisonné ware generally exhibits the quality suggestive of unwearying labour and patience. [10]

It was these qualities of the skills of creating intricate and detailed work that appealed to collectors of that period.

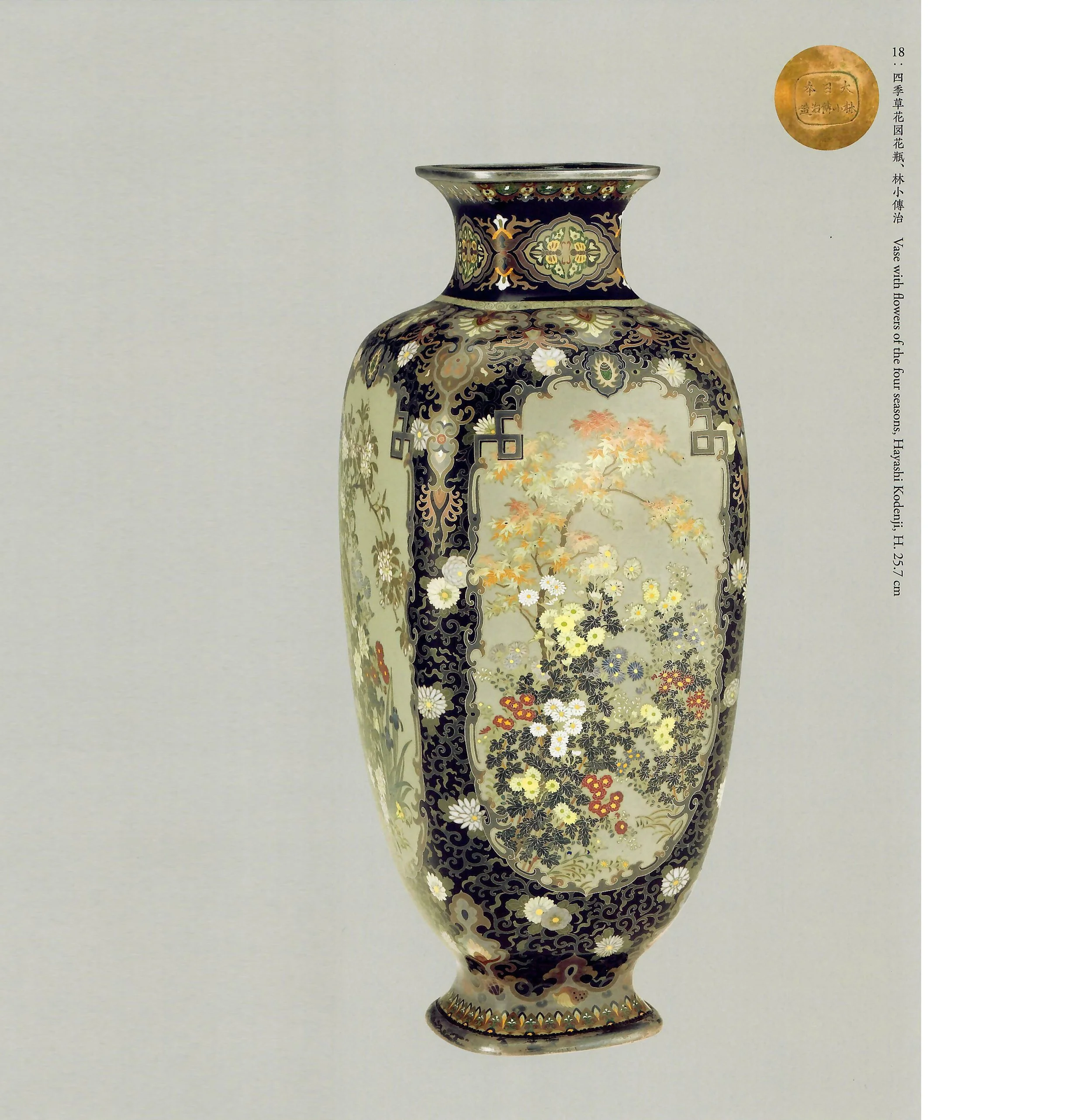

Hayashi Kodenji (1831-1915) was a craftsman who was to become one of the most influential cloisonné makers of his time. Kodenji set up an independent cloisonné workshop in Nagoya in 1862 from where he began to train other enamel workers. He remained at the forefront of cloisonné manufacturing in the Nagoya region throughout his long career. Of the many companies that were also producing in Nagoya and the surrounding area, none was more influential and productive than the Andō Company. Around 1881, Andō Jubei employed Kaji Satarō, grandson of Kaji Tsunekichi as foreman of his company until 1897 when he employed Kawade Shibatarō (1856 - 1921) as his chief technician. It is to Kawade that credit should be given for the many technological innovations in enamel manufacture that made the Andō Company so successful.

Harada mentions Kawade in glowing terms: ‘His [Andō's] reputation was established chiefly by the splendid work turned out by his chief enamel artist and designer, Kawade Shibatarō, who is deservedly considered the greatest enamel expert in the manufacture of shippō at the present time. Perhaps no other living person has done more towards the improvement of Japanese enamels and the invention of new methods of application than Kawade.’ [11] The Andō Company exhibited at national and international expositions winning its first award at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893.

A publicity brochure issued by Namikawa Sōsuke reproduced an article from the New York Herald of February 9th 1896 and includes extracts from interviews with Sōsuke reflecting the state of enamel production in Japan. Captioned ‘Japanese Cloisonné: The great Namikawa, of Tokyo, describes the development of his art in the last two decades', Sōsuke is quoted :

I regret that the widespread demand for Japanese products in your country [America] has created an awkward confusion and lack of discrimination as to what should be classed as commercial commodities purely and what should be given rank as aesthetic creations. For instance, my work is regarded as too expensive, and it certainly is when classed with the ordinary Cloisonné on the market; but I assure you that under my system, when the labour, time, repeated failures, &c., incident to turning out a perfect gem are taken into consideration my valuations are not at all exorbitant. Not a piece leaves my hands that does not represent many attempts and failures and which is not the result of patient toil, well-nigh despairing. [12]

In 1903, the V&A bought its first signed piece bearing the seal of Namikawa Yasuyuki; however, though having a typical ‘Kyoto Namikawa' silver name plaque, this is clearly the work of Shibata, another Kyoto maker. The overall design and execution of wirework does not match the standards of Yasuyuki and is indicative of the tact that faking (or copying) the work of the master enameller was deemed worthwhile and, because even in Yasuyuki's own time his work was expensive, so a piece bearing his silver seal plaque could be seen as more than a simple utsushi. Other enamel objects can be found which have a silver plaque with the mark 'Kyoto Shibata' - which are all but identical in style to that of Yasuyuki. [13] We know nothing of Shibata and many theories have been put forward as to who this mysterious craftsman was, though it is evident that he was based in Kyoto and knew Yasuyuki's work well enough to claim his own works as being by the master craftsman.

Around 1980 there was a worldwide resurgence of interest in the arts of the Meiji period, largely through museum curators in the West, in Japan and the USA re-assessing their collections together with the work of important collectors and connoisseurs such as Mr Murata. It seems that the work of the finest enamel craftsmen of the Meiji period is again entering a 'Golden Age’ and publications such as this book will further and add to our understanding and appreciation of Japanese cloisonné enamels.

1. Harada, Jirō, 'Japanese Art and Artists of Today - VI. Cloisonné Enamels’ The Studio, June 1911, p. 2712. Brinkley Captain F., ‘Japan, its History Arts and literature: Vol. VII Pictorial and Applied Art; Vol. VIII Keramic Art’, Boston and Tokyo: Tokyo edition (limited edition number 199), 1901, p.334 3. ‘The commencement of the collections forming the Art Museum dates from the year 1846, when a committee, appointed by the Board of Trade, recommended that a Museum should be ‘formed in connection with the School of Design at Somerset House…’ From the Inventory of the Objects Forming the Art Collections of the Museum at South Kensington', issued by the Science and art Department of the Committee of Council on Education, London, 1863, pp. iii, iv4. For further images of the Vienna displays see ‘Expositions of the Early Meiji Period: Encounter East and West’ (vars. authors) in ‘Japan Goes to the World’s Fairs: Japanese Art at the Great Expositions in Europe and the United States, 1867-1904’, Los Angeles County Museum, 2005, pp. 24-65. Alcock, Sir Rutherford, Art and Art Industries in Japan, London, 1878, p.1906. Dresser, Christopher. ‘Japan, its Architecture, Art and Art-Manufacturers’, Longmans, Green, and Co. London 18827. Kipling, Rudyard: ‘From Sea to Sea and other sketches’, MacMillan & Co., London, 1904, pp. 387-98. Ponting, Herbert: ‘In Lotus Land Japan’, London, new and revised edition, 1922, p.2349. ibid, p.24110. Harada, p.27111. ibid, pp.282-312. Pamphlet in the collection of Mr Malcolm Fairley, London13. Schneider, Frederick T: ‘The Art of Japanese Cloisonné Enamel’, McFarland & Co., Jefferson, North Carolina and London, p. 240 for further discussion on Shibata