The Yuzen Technique: History and Innovation in Japanese Textile Art

Figure 1

:

A yuzen dyed and painted silk hanging, depicting Avalokita standing holding a lotus flower and with Kannon holding a ruyi sceptre seated on the back of a foo dog, within a silk brocade border.

Unsigned Meiji Period, circa 1880

Yuzen dyeing emerged in the middle of the Edo period, in the late 17th century. Named after Miyazaki Yuzensai, a fan painter whose designs captured the imagination of people across all social classes. This technique revolutionised Japanese textile decoration by allowing artisans to create detailed pictorial designs that resembled painted artworks rather than the repetitive patterns characteristic of traditional weaving and dyeing methods.

The Development of the Yuzen Technique

The fundamental innovation of yuzen lay in its use of resist paste to draw pattern outlines, followed by direct brush application of dyes to create fine details. This process allowed for unprecedented freedom in design enabling the expression of complex motifs and subtle gradations that had been impossible with conventional techniques like embroidery, weaving and shibori (tie-dyeing).

The technique involved several precise steps requiring exceptional skill. First, the artist drew the design onto silk using colouring matter derived from aobana plant sap (dayflower), which would wash away later. A resist paste made of rice starch, rice bran and lime was then applied in detailed lines using a cone-shaped tool called a tsutsu, similar to a pastry chef's piping technique. This paste created barriers that prevented dyes from bleeding across design boundaries, leaving the design areas exposed for colouring.

Colours were then carefully painted into the spaces enclosed by the dried paste ridges using brushes ranging from broad washes to hair-thin detail brushes. The dyeing process often involved multiple applications, building up colours gradually to achieve the desired depth and subtle colour transitions. Different sections may be masked during specific dyeing stages to maintain precise colour boundaries. The colours were then fixed through steaming, after which the background starch was rinsed off in clean water. If ground colouring was required the design areas were covered with resist paste and the entire fabric was dyed with the desired background colour. This process might be repeated several times depending on the complexity of the design. The precision required at each stage made traditional yuzen extremely time-consuming and expensive but its ability to create pictorial designs without fading when immersed in water, whilst maintaining the silk's natural texture made it highly desirable. Importantly, yuzen also complied with the Shogunate's sumptuary laws, which were particularly significant during this period.

The Edo period sumptuary edicts attempted to control "appearance" and regulate the expenditure of wealth according to social class. As merchant families began amassing large fortunes and adopting lifestyles previously reserved for the samurai class, the bakufu (shogunate government) issued these laws to reinforce class distinctions and encourage frugality. The government was especially concerned that ostentatious displays of wealth among the merchant class would undermine samurai morale and discipline. These regulations placed strict limits on luxurious entertainment and consumption, closely correlating what was appropriate for each social level. Fashion was recognised as a means of crossing class boundaries, so clothing styles and accessories were heavily regulated. The sumptuary laws specifically prohibited elaborate embroidery and complex shibori (tie-dyeing) techniques, making yuzen an attractive alternative for wealthy merchants seeking beautiful textiles within legal bounds.

Figure 2:

A Japanese yuzen birodo (cut velvet) panel depicting a thatched hut beneath bamboo on the banks of a river in a mountainous moonlit setting.

Meiji period, circa 1900

The Meiji Period Revival

By the end of the Edo period yuzen had declined significantly, used primarily for wealthy merchants' wedding garments and court ceremonies. The technique faced near extinction with very few craftsmen remaining by the early Meiji period. However this changed dramatically through the efforts of innovative textile merchants, particularly the 12th Nishimura Sozaemon (1855-1935) of the company that would become known as Chiso.

Around 1873 Sozaemon approached the Japanese painter Kishi Chikudo (1826-1897), requesting that he create designs for yuzen work. This was considered unconventional as yuzen designs were typically created by artisans rather than recognised artists. After considerable persuasion Chikudo agreed and became an advisor. He was soon joined by other prominent painters including Imao Keinen (1845-1924), Kono Bairei (1844-1895) and Mochizuki Gyokusen (1834-1913).

This collaboration completely transformed yuzen design. The realistic expressions, delicate details and sophisticated compositions created by these Japanese painters gained widespread popularity and renewed interest in the technique. This reform occurred just as the government was beginning to recognise the importance of design in craft production, making it remarkably prescient.

The Meiji period also saw significant technical developments in yuzen production. The introduction of imported chemical dyes enabled the creation of colours difficult to achieve with traditional vegetable dyes, while making production more efficient and affordable. A technique called utashi yuzen was developed, involving the mixing of chemical dyes in trays for application, initially used for children's clothing and gradually expanding to women's outerwear.

Figure 3: Nishimura Sozayemon

A yuzen birodo (dyed and cut velvet) textile depicting the Kiyomizu-dera temple in summer, within a carved wood frame, the reverse bearing the original paper label explaining the technique of yuzen birodo

Meiji period, circa 1900

Yuzen-Birodo

Perhaps the most significant innovation was the creation of yuzen-birodo in around 1868. Nishimura Sozaemon oversaw the development of this technique, applying yuzen dyeing to birodo (velvet), creating an entirely new product for both domestic and export markets (see fig.4). The process involved painting designs onto woven but uncut velvet, which was woven by passing threads over fine metal wires running parallel to the woof. After the yuzen dyeing and steaming process, threads in specific areas were carefully cut with small knives to form tufted pile while background areas remained as horizontal ridges without cutting.

Applying yuzen to velvet presents additional technical challenges due to the fabric's pile structure. The velvet's raised pile surface affects how both resist paste and dyes interact with the fabric. The resist paste must penetrate between the fibres without matting the pile, requiring modified application techniques. Dye application also needs adjustment to account for how the pile structure affects colour absorption and the way light reflects off the surface.

This selective cutting technique created dramatic three-dimensional effects with varying textures and depths that enhanced the pictorial quality of the designs. The technique allowed for sophisticated manipulation of perspective and depth, making full use of the detailed sketches provided by the Japanese painters, a technique that could be cleverly done to enhance the sense of depth and perspective in a picture (see fig. 2 & 3).

Figure 4: Chiso Manufacture Label

“How the Well-Known Yuzen-Birodo, or Cut-Velvet is made”

Inventor and Manufacturer: Sozayemon Nishimura, Kyoto, Japan

Taken from the back of textile fig.3

“The Yuzen-Birodo, better known as Cut velvet is not painted work as it appears to be. The pictorial effect produced hereon is obtained by a special process of dyeing invented by the artist Yuzen who flourished in the latter part of the 17th century, hence the name Yuzen Dyeing.

In course of weaving the fabric, the slender metallic wires running parallel with the woof, become covered with threads. The required patterns and designs are dyed into the fabric thus produced, by the Yuzen process: the colours obtained being quite durable. When the dyeing is finished, each thread covering the wires woven into the texture, is carefully cut over the picture produced; while the ground of the fabric is left plain without the cutting. The wires are then extracted and the work is completed.”

Exhibition Success and Recognition

Chiso presented yuzen dyeing at the Kyoto Exposition as early as 1875, winning a silver medal for Progress with a yuzen hanging. By 1878 they had won a silver cup at the 7th Kyoto Exposition and in 1879 their "Kamogawa Dye" won a gold medal at the 8th Kyoto Exposition.

The yuzen-birodo technique gained international recognition when exhibited at the Second Domestic Industrial Exposition in 1881 where it won first place in the Progress category. The technique's success culminated at the Paris World Exposition in 1900 where pieces were ordered by the Imperial Household Ministry as official gifts. At this time Chiso operated dozens of factories in Kyoto with 380 workers involved in production.

Wartime Challenges and Preservation

As Japan entered the Showa era and became increasingly militarised, the production of luxury items like kimonos became severely restricted. In 1940 the Ministry of Commerce, Industry, Agriculture and Forestry enacted the "Luxury Goods Manufacturing and Sales Restriction Ordinance," which effectively eliminated business freedom for textile producers. Recognising the threat to traditional techniques, Governor Kyoshiro Ando of Kyoto Prefecture instructed the 13th Nishimura Sozaemon (1890-1955) to establish a preservation system for Kyoto's yuzen traditions.

Despite the challenges of wartime with many craftsmen called to war, requisitioned to munitions factories or evacuated, Chiso established the "Nishimura Dyeing Research Institute" in 1943. The company received certification from the Japan Arts and Crafts Control Association as a "Craft Technique Preserver," allowing them to continue limited production (maximum 600 items annually with a production value not exceeding 200,000 yen). This designation was crucial for maintaining the skills and knowledge necessary to preserve yuzen techniques through the war years.

The post-war period brought additional challenges when silk production was frozen from 1945 to 1949, delivering a major blow to the entire textile industry. However Chiso worked to reorganise and adapt to the new economic situation. As Japan's economy recovered the company focused on refining and preserving the yuzen techniques that had been maintained throughout the war years, ensuring the continuation of this traditional art form.

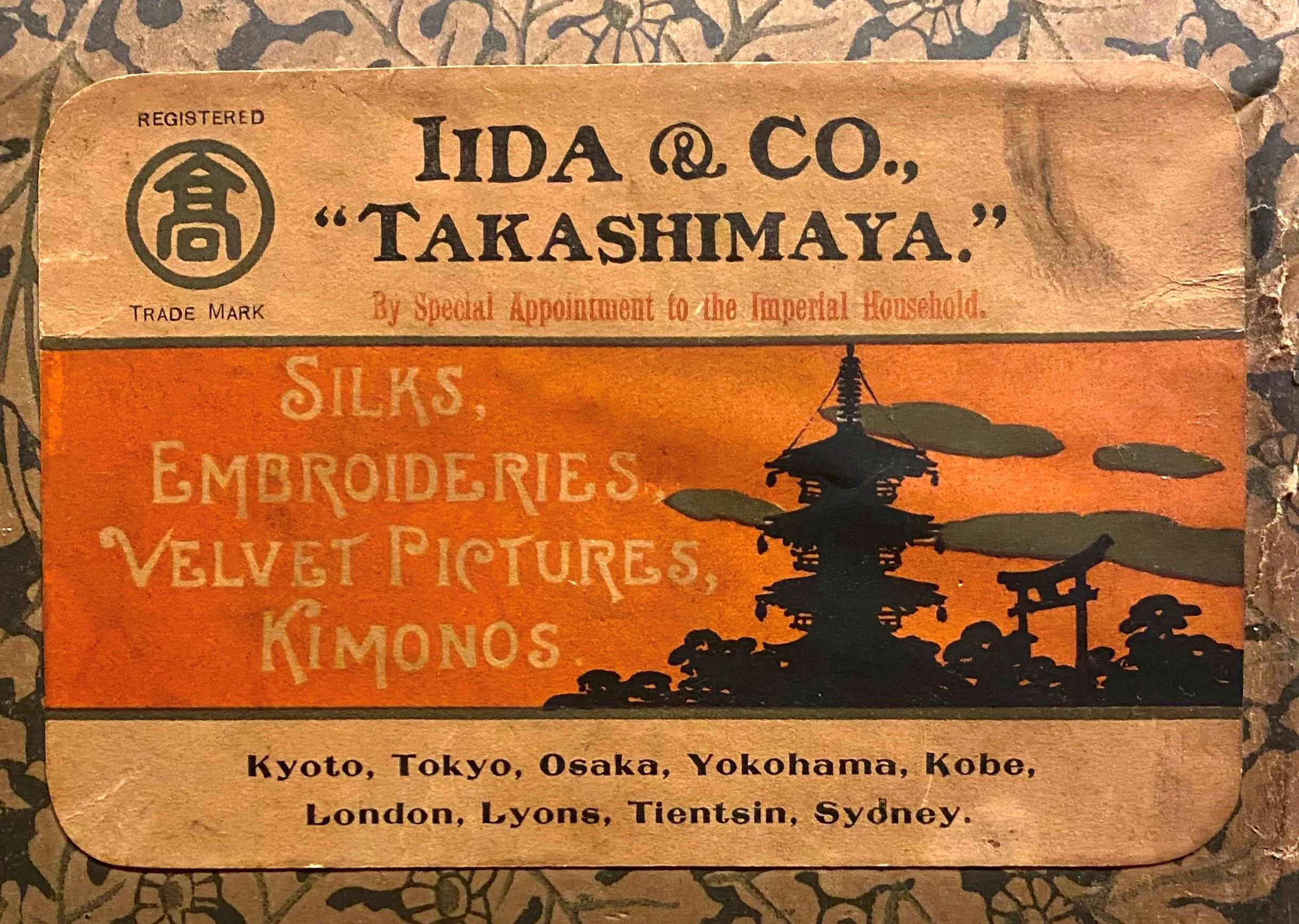

Other Major Producers

Chiso was not the only major producer of yuzen textiles during this period. Takashimaya, under Iida Shinshichi, also became a significant manufacturer of yuzen and cut velvet works, exhibiting at the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago. Both companies contributed to the development and popularisation of these techniques for both domestic and western export markets (see fig. 5), with Takashimaya later introducing design competitions in 1891 to encourage innovation in patterns.

Another notable producer was Hirooka Ihei, head of a well-known Kyoto yuzen silk merchant house. Hirooka exhibited successfully at domestic exhibitions and in 1897 pioneered the musen (lineless) yuzen technique, which enabled the creation of soft wash effects popularised by Nihonga painters. This innovation eliminated the characteristic resist lines, allowing for more painterly effects that aligned with contemporary artistic trends.

Figure 5:

Takashimaya Manufacture Label

Artistic and Cultural Impact

The revival of yuzen during the Meiji period was closely connected to the broader promotion of painting education and arts and crafts. The establishment of the Kyoto Prefectural Painting School in 1881 and the Kyoto Art Association in 1890 created institutional support for the collaboration between painters and craftsmen that had revitalised yuzen design.

These yuzen textiles from the Meiji period were created as artworks in their own right, intended for display and appreciation rather than functional use. They varied widely in size, from small intimate pictures suitable for domestic display to larger compositions for more formal settings. The technique's ability to reproduce designs with remarkable fidelity made it particularly suitable for translating the sophisticated compositions of Japanese painters into textile form.

Figure 6:

A yuzen (cut velvet) panel depicting the Yomeimon gate of the Nikko Toshogu shrine

Unsigned, Meiji period, circa 1900

The Meiji Period as the Golden Age of Yuzen

While yuzen dyeing techniques were established and used throughout the Edo period, it was during the Meiji era that the art form reached its highest level of sophistication and artistic achievement. The major textile manufacturers, particularly Chiso and Takashimaya, transformed what had been a declining craft into an internationally recognised art form through systematic innovation in both technique and design.

The collaboration between established textile houses and prominent Japanese painters created an unprecedented fusion of traditional craft techniques with contemporary artistic vision. The development of yuzen-birodo and other technical innovations, combined with the introduction of chemical dyes and more efficient production methods, enabled the creation of works that surpassed anything achieved during the technique's original Edo period development.

The Meiji period's emphasis on artistic education, international exhibition and technological advancement provided the perfect environment for yuzen to evolve from a luxury craft into a sophisticated art form. Through the efforts of companies like Chiso and Takashimaya, supported by the institutional framework of art schools and cultural associations, yuzen achieved a level of technical mastery and artistic recognition that established its reputation as one of Japan's premier textile arts. The preservation efforts during wartime and post-war recovery further demonstrate the commitment to maintaining these elevated standards, ensuring that the Meiji period innovations in yuzen would continue to influence the art form for generations.

References

McDermott, Hiroko. & Pollard, C, Threads of Silk and Gold: Ornamental Textiles from Meiji Japan, The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 2013

Brinkley, F., 1841-1912, “Artistic Japan at Chicago: A description of Japanese works of art sent to the Works in Metal, glyptic works, textile fabrics, lacquer, enamel, pictures, por…,” publ. Yokohama, Printed at the “Japan Mail” office. 1893, P.9-12

Chiso Co., Ltd. A history of CHISO: 460 years of tradition and innovation, Kyoto, 2015

Noma, Seiroku, Japanese Costume and Textile Arts, New York, 1974, p.155-157